Vaccinating Only The ‘Critical Mass’ For Covid Herd Immunity: Is It The Right Option For India?

Not everyone in India will get the COVID-19 vaccine! Yes, you heard it right. The Centre announced its “critical mass” plans at a Union Health Ministry briefing last week where it took a U-turn on Prime Minister’s promise that “everyone will be vaccinated”. On December 1, Health Secretary Rajesh Bhushan said that the government has never spoken about vaccinating the entire country against COVID-19. Adding to that, Director-General of ICMR Dr. Balram Bhargava said: “If we’re able to vaccinate a critical mass of people and break virus transmission, then we may not have to vaccinate the entire population.”

Vaccinating a “critical mass” would mean giving the Covid vaccine to enough people that the chain of transmission is broken — or effecting “herd immunity” in the population. Clearly, the government has shifted its focus from vaccinating the entire population to achieving ‘herd immunity’ as it aims, in the first instance, to vaccinate 250-300 million ‘priority’ populace in six months after a vaccine is available. If the earlier presumption was that all would be given the shots, what does this mean? Is it possible? And, what are the challenges? Let’s look into it in detail.

According to sources, the “priority” populace of the government would include healthcare workers such as doctors, nurses, paramedic staff, frontline workers like sanitation staff, security personnel, the elderly, and those with comorbidities. Together, they make up the critical mass. However, we still do not have a clear picture regarding the threshold of such immunity. Usually, highly infectious diseases have a high threshold. This includes measles, and chickenpox, among others.

The government’s idea of vaccinating a “critical mass of people” for the purpose of breaking the virus transmission chain is certainly riddled with challenges. Experts in the field doubt the move since the current lot of promising Covid vaccines aren’t the ‘sterilising’ type. This means that they won’t stop the novel coronavirus from entering the cells of a vaccinated individual — all they promise to do is prevent the infection from taking on a severe form. These vaccines, they say, would at best shrink a Covid-infected person’s window of infectivity — the amount of time they serve as a carrier of the virus — rather than closing it altogether. Breaking the chain of transmission becomes difficult in such a situation, experts say.

“For the initial infection to be blocked, we need inhaled mucosal vaccines which produce secretory IgA antibodies. Those vaccines are still under early evaluation. The injectable vaccines may limit the period of infectivity by preventing a severe infection but not fully guarantee stoppage of transmission even for a limited period from a vaccinated person who acquires the virus,” said Dr. K. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) and member of the International Steering Committee of the WHO Solidarity Trial, which is aimed at finding an effective treatment for Covid-19.

“For that reason, it is difficult to predict what percentage of people need to be immunised to be assured of breaking the chain of transmission. If the main goal is to prevent severe illness and death, as it must be, all vulnerable persons in the population must be prioritised for immunisation,” said Dr. Srinath. “Disrupting the chain of transmission through limited immunisation coverage is a possible but uncertain outcome,” he added.

Also, the levels of immunisation needed for herd immunity are determined by how the virus spreads in the population and makes the assumption that spread is homogenous. But SARS-CoV-2 virus spread exhibits a high level of uneven transmission. This is the reason why there has been a number of super-spreading events where some infected individuals spread the virus to a very large number of people while most infected individuals transmit the virus only to a few or none.

In addition to all this, new research on herd immunity carried out by researchers at the University of Texas and The Santa Fe Institute has claimed that the threshold of such immunity is much higher than previously speculated. For the new study, published in the journal medRxiv, researchers studied the two forms of mitigation curves ― timing and magnitude of transmission reduction via non-pharmacological interventions.

Their new mathematical model found that Covid-19 herd immunity estimates are as high as 60 per cent to 80 per cent. This reveals that a high proportion of the population needs to be immune to the infection, either by getting infected (active immunity) or by vaccination, to protect the remaining non-immune population. This finding has significant implications on present policies that propose relaxing the mitigation measures, said the researchers.

The World Health Organization experts have also pointed to a 65%-70% vaccine coverage rate as a way to reach population immunity through vaccination. However, the Health Ministry of India while declaring the different stages of vaccination, has suggested that vaccinations would only be provided to about 300 million people in the initial phase, accounting for about 23 per cent of India’s population.

Last but not the least, considering that the government has already listed out the high-priority groups that will receive the vaccine, the issue of choosing other sections of the population that needs to be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity will be ethically challenging. Objective, transparent processes for making priority-setting decisions are extremely important to maintain trust in the vaccination plans. These should be communicated publicly, including the rationale for the choices, and there should be a mechanism of appeal.

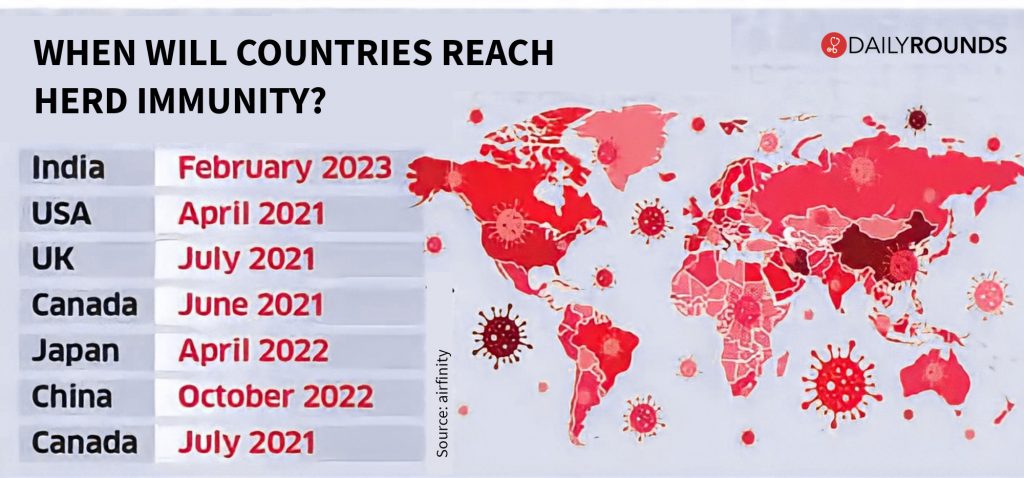

However, according to a research report by Airfinity, a London-based science analytics company, India will attain herd immunity with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic no sooner than February 2023. According to Airfinity’s forecasts, the US and Canada are expected to attain herd immunity by the second quarter of the calendar year of 2021, while Japan is likely to do so in April 2022.

While India is expected to be the second-biggest producer of COVID-19 vaccines by the end of 2021 with 2.75 billion doses, the US would still be ahead at 2.77 billion doses, the report further reads. For qualitative factors assessed in making the forecasts, it is India’s lack of guidance on vaccine purchases, and of a coherent vaccination list that makes the country one of the last to attain herd immunity, despite having been majorly involved in the production process.

The findings certainly indicate that there’s still a long way to go before getting anywhere close to ‘herd immunity’ through the vaccination of limited populace. And the challenges in front shows that the journey may not be as smooth as anticipated by the policymakers.

Follow and connect with us on Twitter | Facebook | Instagram