Should We Worry About COVID-19 Reinfection? Here’s What We Know So Far

As we are approaching the probable one-year anniversary of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 infecting the first human, experts are faced with yet another critical question: can a person catch the disease more than once? The answer to this question influences, among other things, the prospects of the vaccine and its ability to protect us from the disease.

To date, there have been around 25 verified cases of COVID-19 reinfection, with various other unverified accounts from around the world. Although this is a comparably small fraction of the millions of people known to have been infected, should we be concerned? To unpick this puzzle, let’s look into it in detail.

The first confirmed case of Covid-19 reinfection was reported by researchers at the University of Hong Kong in the last week of August. A few other anecdotal cases of reinfection have since emerged, including a few in India. In late August, BNO News, an international news agency headquartered in the Netherlands, established the COVID 19 Reinfection Tracker which currently lists 24 confirmed cases.

According to the tracker, the US state of Washington is presently investigating about 120 suspected cases of reinfection. In Brazil, health officials are reportedly investigating 247 possible cases and a retrospective study in Mexico found 258 suspected cases of reinfection, which included 11 deaths. As none of the Mexican cases were confirmed with genomic sequencing, the tracker has not listed them.

Other countries with cases listed on the tracker include India, Belgium, Qatar, Ecuador, Spain, and Sweden. These confirmed cases highlight the fact that natural infection with COVID-19 does not confer solid immunity as would occur after an infection with measles.

Infection with SARS-CoV-2 leads to a detectable immune response, but the susceptibility of previously infected individuals to reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is not well understood. SARS-CoV-2 infection results in the generation of neutralising antibodies in patients. However, the degree to which this immune response indicates a protective immunity to subsequent infection with SARS-CoV-2 has not yet been elucidated.

In studies of immunity to other coronaviruses, loss of immunity can occur within 1–3 years. Cases of primary illness due to infection followed by a discrete secondary infection or illness with the same biological agent can best be ascertained as distinct infection events by genetic analysis of the agents associated with each illness event.

Let’s look into the case report of an individual, published in ‘The Lancet’ journal, who had two distinct COVID-19 illnesses from genetically distinct SARS-CoV-2 agents. The 25-year-old man who was a resident of the US state of Nevada presented to health authorities on two occasions with symptoms of viral infection.

The patient had two positive tests for SARS-CoV-2, the first on April 18, 2020, and the second on June 5, 2020, separated by two negative tests done during follow-up in May 2020. Genomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 showed genetically significant differences between each variant associated with each instance of infection. However, the second infection was symptomatically more severe than the first.

Genetic discordance of the two SARS-CoV-2 specimens was greater than could be accounted for by short-term in vivo evolution. These findings suggest that the patient was infected by SARS-CoV-2 on two separate occasions by a genetically distinct virus. Thus, the study shows that previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2 might not guarantee total immunity in all cases.

It had been assumed that the second round of Covid would be milder, as the body would have learned to fight the virus the first time around. However, it is still unclear why the Nevada patient became more severely ill the second time. One idea is he may have been exposed to a bigger initial dose of the virus. It also remains possible that the initial immune response made the second infection worse. This has been documented with diseases like dengue fever, where antibodies made in response to one strain of dengue virus cause problems if infected by another strain.

It is too early to say for certain what the implications of these findings are for any immunisation programme. But these findings reinforce the point that we still do not know enough about the immune response to this infection.

Reinfection In India

On September 15, 2020, researchers from the Government Institute of Medical Sciences, Greater Noida, and the Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology (IGIB), New Delhi, uploaded a preprint paper confirming two cases of reinfection from India. The patients – a 25-year-old male and a 28-year-old female, both healthcare workers in the Noida hospital – got infected with a different variant of the virus the second time, about three and a half months after their first infection.

Following this, the IGIB team also confirmed reinfection in four Mumbai healthcare workers using whole-genome sequencing. The preprint published on the Lancet journal’s website shows that all four had a more severe COVID-19 infection compared to their earlier episode. “For all four healthcare workers, the second episode had more symptoms with constitutional manifestations and illness that lasted longer than the first episode” the paper reads.

While the first COVID infection was asymptomatic to mild in these healthcare workers, all needed hospitalization the second time around. In fact, one of the patients received convalescent plasma therapy and another was unable to return to routine activities and work for almost three weeks.

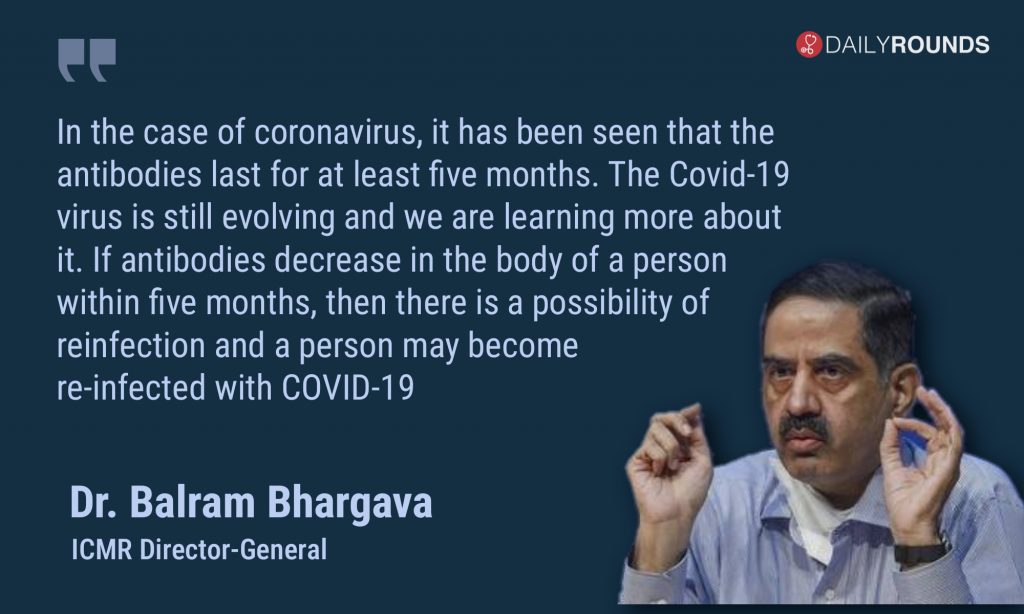

The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) on Tuesday confirmed that patients who have recovered from Covid-19 can again get infected by the virus once the antibodies of the viral disease start depleting. There is a possibility of re-infection if antibodies reduce in the body of a Covid-19 recovered person in five months’ time after the recovery, the ICMR said.

Dr. Bhargava also informed that the ICMR is conducting an assessment on the subject of reinfection as commissioned by the Union Health Ministry, and its result will be out shortly. As per the ICMR, so far, three cases of reinfection have been reported in the country — two from Mumbai and one from Ahmedabad.

According to the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), you call it reinfection (of Covid-19) if the person is reinfected after 90 days from turning negative to the SARS-CoV-2 after testing positive to it. However, the apex body of medical research in India had stated that the cut-off date for the depletion of antibodies set by it for the assessment is 100 days from the infection. “There are various cut-off days that are being referred to for reinfection. Though the public is going by up to 110 days, we are taking 100 days as the cut-off period because the antibodies last until then,” said Bhargava.

The COVID-19 reinfection offers a rich area for research and raises questions not only about immunity but also about the impact of dose size and the virulence of the viral strain. There are implications for vaccines as well. Although vaccines can elicit more potent, more durable immune responses than natural infections, these cases certainly suggest that a once-off vaccine may not last a lifetime and boosters may be required.

Against 40 million cases of infection worldwide, the 25 reinfections make it appear an extremely rare event. But experts say it is too soon to know whether these few are the tip of a yet to be revealed iceberg! Let’s hope it’s not.

Follow and connect with us on Twitter | Facebook | Instagram