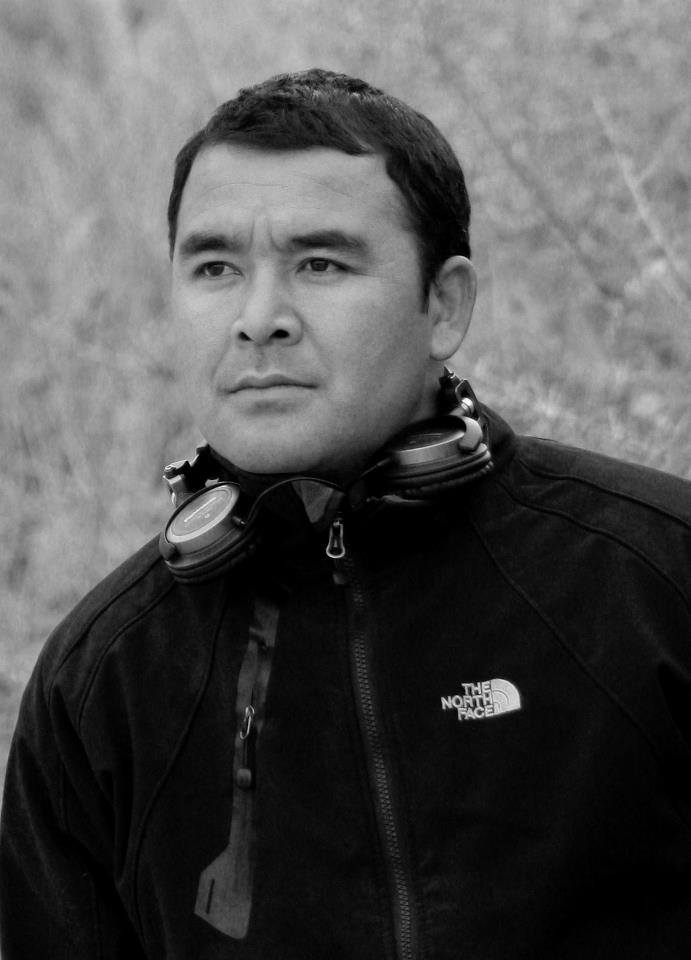

Meet the ‘Nomadic Doctor’ of Ladakh, who saved the lives of 1000 women

Everybody will have a turning point which can change the course of their life. Dr Nordan Otzer had two major turning points in his life, which changed his dreams for good.

Everybody will have a turning point which can change the course of their life. Dr Nordan Otzer had two major turning points in his life, which changed his dreams for good.

The year was 2007. Dr Nordan was working in a Tamil Nadu rural hospital. One day, he received news that his mother has cervical cancer, which, by that time spread to her liver. Dr Nordan rushed home as soon as he heard this news. Unfortunately, she passed away within one month of diagnosis. That was the first turning point in Dr Nordan’s life.

He was planning to work in a big hospital and settle abroad till then. But after this incident, he went home to his village of Hunder in Nubra Valley and joined nearby district government hospital as a medical officer.

The second turning point of his life happened while working in the district hospital.

“One day, I received a call from Mr Ishey Tundup, the principal of a school in Leh. He was unable to track down one of his students, Sonam Dolma,” he recalls. “Dolma’s right leg had been amputated below the knee, as she had bone cancer. She was in devastating pain, and I couldn’t withstand the feeling of helplessness I felt. We spoke to the parents and talked about getting her treated in Delhi, and assured them that we would find a sponsor,” says Dr Nordan. Dr Nordan did find a sponsor and took her to Delhi. There the doctors amputated her legs below the hips and she was recovering well. Suddenly, things got worse and she died.

That’s when Dr Nordan thought enough is enough. He says people needed to know more about their body and physical health, especially women, with regards to reproductive health. He believed this needed to change and started his ‘nomadic’ journey, spreading awareness of modern medicine in this remote corner of India.

But in Nubra, there were more challenges to be solved. “When I would talk about the cervix or breasts, these women would look down in shyness. However, looking into their eyes, I could sense that they were grateful that someone was talking about these issues and raising awareness amongst them. Through this one-year outreach initiative, I met nearly all the women residing in Nubra. I spoke to them about the symptoms of breast or cervical cancer and the need for regular checkups, screening and treatment,” he says. He sought the help of some gynaecologists in Singapore as well. When it came to the screening, hundreds of women turned up, even those who were healthy and had no symptoms or health issues. Started in 2010, the team of doctors led by Dr Nordan has screened around 10,000 women from across Ladakh in the last nine years and 1,000 among them had precancerous lesions. The team operates under the banner of Himalayan Women’s Health Project.

Dr Quek Swee Chong, a Singapore-based specialist in Obstetrics and Gynecology, who helped Dr Nordan in this initiative said that there is a very non-invasive, low morbidity, painless and simple procedure to treat these precancerous lesions. It’s called the screen-and-treat approach. Speaking about his experience, he says that the first few years involved fact-finding, getting a feel of the level of disease prevalence, and establishing trust with the local population.

These camps happen every year with the latest one happening three weeks ago in Nubra. “I lost my mother at a young age, and believe that no one else should go through what I did. The solution to our problems is that if people know more about their bodies, they can prevent a majority of the diseases. That is why I do the work I do,” he says.

He also succeeded in making Nubra a Tobacco-Free Zone. Working alongside the Women’s Alliance of Ladakh, a voluntary women’s organisation, and other mothers in the region, Dr Nordan helped raise awareness among the local communities about the dangers of tobacco addiction, particularly for young adolescents. In the meantime, he began his outreach work in remote corners of Ladakh, which have no access to medical services. There, Dr Nordan and his team would conduct free health check-ups and distribute medicines as well. To pay for these free medicines, he took a bank loan in 2012 to start a restaurant and cafe in Leh.

“Whatever profit I make from these enterprises, it goes into buying medicines, which I distribute for free. Considering my family’s secure financial condition, I don’t have to save any of the money I’m making. I can use that money for social service,” he says.

Source: The Better India.