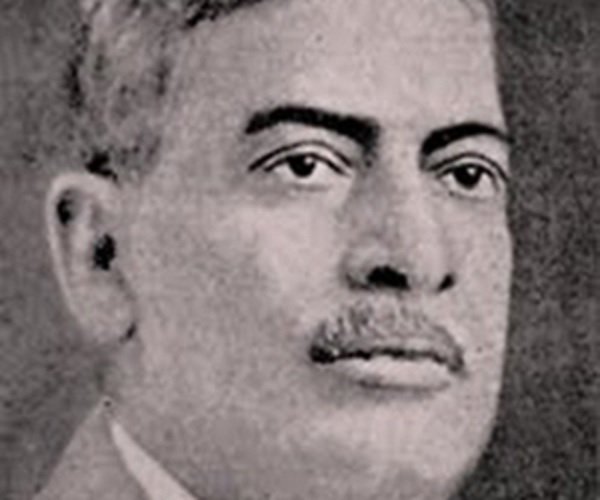

Legendary doctor- under appreciated in life, forgotten after death

Upendranath Brahmachari was one of the most legendary medical practitioners that India has ever known. Sadly enough, his name is not familiar to most in this day and age.

He was brought up in a family that already had a medical practitioner-his father who was a physician with the East Indian Railways. Upendranath-who was was born in West Bengal in 1873 wanted to set on a career in mathematics during his student years. But one of his instructors urged him to choose medicine instead.

It was in 19o0 that he graduated in medicine and a few years down the line he obtained his MD and a PhD- not a small task, especially considering the era in which he did this.

After completing his education Upendranath joined the Provincial Medical Service- this in addition to teaching at the Dacca Medical School.

Nobel-worthy?

During this time, an Austrian professor of Medicine, Julius von Wagner proposed that tertiary neurosyphilis could be successfully treated if you inject malarial parasite into the patient’s blood stream. Antibiotics were not yet discovered and for parasitic infections the only treatments were quinine for malaria and arsenic to tackle syphilis.

Wagner’s idea earned him the Nobel Prize in 1927.

However, critics of are of the opinion that Brahmachari’s contribution to the medical profession was far more significant and hence deserving of a Nobel.

During Upendranath’s time Kala-azar epidemics were all too common and sometimes wiped out entire villages. It’s said that each year, literally millions of lives were lost due to the deadly disease which lacked a known treatment.

It was Brahmachari who came up with the idea of using urea stibamine as a treatment: an idea that contributes to saving of millions of lives even today.

In fact, Brahmachari was nominated twice for the Nobel Prize in Medicine and Physiology- both in 1929 and 1942. It’s widely believed that one of the reasons why he wasn’t awarded the prize was due to his ethnic origins.

Even more contributions but little recognition

Brahmachari’s contributions to medicine went further- he was the one to establish Asia’s very first blood bank in Calcutta.

Notwithstanding such extra-ordinary achievements, he was never elected to the Royal Society or the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In fact, when the Indian National Science Academy came into being, he wasn’t even considered for the Fellowship.

In an age when India is emerging as a leader in medical tourism and care, hopefully he would get the recognition that was denied him in life.