The most recent round of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership(RCEP) was held in Japan in early March.

One of the key aspects of this year’s RCEP was the insistence by developed nations to add provisions which will impact negatively the production of cheaper medicines. If these provisions are added, it could badly affect India’s Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme.

The RCEP is a trade deal which is being negotiated among 10 ASEAN nations and their partners- China, India, Australia, New Zealand, S. Korea and Japan. The negotiations are riding a rough wave since developed nations are pushing for intellectual property protections.

As per one of the delegates in the negotiation, “Developed countries are pushing the most for the clause related to data exclusivity. Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia and South Korea already have data exclusivity in their countries. The pressure is on other countries including India.”

Data exclusivity means that clinical trial data produced by one company shouldn’t be used by another to get approval for marketing general versions of the drug. This practically makes it impossible for companies to make cheap generic medicines since the clinical trials would have to be repeated at high costs.

India’s stand in this regard would be crucial since the nation is a key source of affordable generic medicines for middle and low income nations.

Adverse clauses

Aside from data exclusivity, the current draft of the RCEP also features many other damaging clauses. The RCEP represents 45% of the global population as well as 40% of the global trade. A leaked text shows that provisions which are backed by S.Korea and Japan could block access to cheaper medicines from India.

Two provisions (other than data exclusivity) are pointed out by health activists as worrying. As per TRIPS (Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights- a global agreement on intellectual property between member nations of WTO) a new medicine could be patented for 20 years. However, the RCEP has extended this period to 25 years. And then, there’s the clause which allows pharma firms to sue governments under an investor-state dispute settlement. This would give the companies the potential power to ask for huge financial compensation and eliminate competition.

Ukraine in a case in point. That nation allows data exclusivity.

Recently, the government was sued by a pharma company in America for allowing the sale of Sofosbuvir which is used to treat hepatitis C. The company sued Ukraine for $4 million and the drug’s generic version-manufactured by an Egyptian company was forced out of the market. The country’s hepatitis treatment program covers just around 2,000 people while over 44,000 people need the treatment urgently in the country.

Impact on India

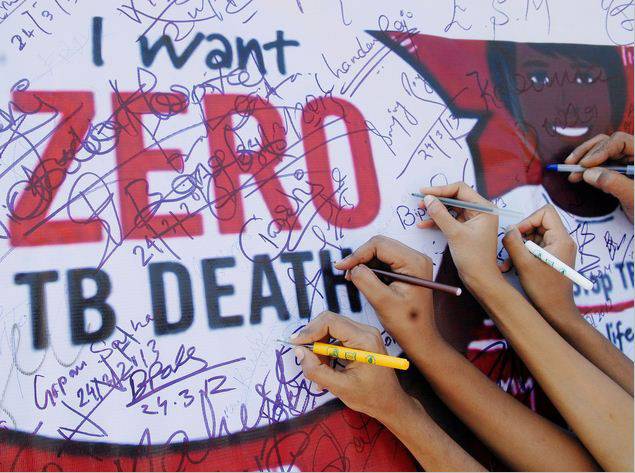

If the provisions are passed in the RCEP deal, India would have a tough time in reaching its goal of eliminating TB. The provisions would render new medicines expensive for a long time.

Two new TB drugs- Delamanid and Bedaquiline have been discovered after forty years. Both of these are patented drugs and the government will need to buy them to scale up treatment for drug-resistant TB. Presently, the cost of DR-TB(without the new drugs) is between Rs. 60,000 and Rs. 2,70,000. The cost of Bedaquiline is Rs.60,000 for a course while Delamanid is around Rs 1,02,000. This means that the total cost for effective treatment would fall between Rs 2,22,000 and Rs. 4,32,000.

600 Bedaquiline courses have been donated to India by the UN’s programme on HIV/AIDS. But when these courses are over, the government would have to start buying medicines.

Delamanid is produced by Otsuka- a Japanese company. It’s expected to get registered in the subcontinent in four or five months. Otsuka has held on to the patent for the last eight years without registering in India- ensuring that no competition pops up with generic production. (Indian companies can’t apply for a manufacturing license for an unregistered drug). If clauses like data exclusivity is approved, then cheaper production of the medicine would be impossible.

That would mean India having to buy both the drugs at high prices from the companies. And for a country which has one of the most pressing TB problems, such a thing could be disastrous.

Image credits: timesofindia.indiatimes.com