Antibiotic resistance burden in India: The bitter truth

Most of the people living in our country might be directed to take antibiotics even for basic ailments, like the common cold, headache, fever etc, right? WHO has identified Antimicrobial Resistance(AMR) as one among the ten threats to global health in 2019. Antibiotic resistance is, of course, a threat to the global level, but nowhere is it as dreary as in India. AMR is a public health problem, which can shake even the foundation of modern health-care.

Most of the people living in our country might be directed to take antibiotics even for basic ailments, like the common cold, headache, fever etc, right? WHO has identified Antimicrobial Resistance(AMR) as one among the ten threats to global health in 2019. Antibiotic resistance is, of course, a threat to the global level, but nowhere is it as dreary as in India. AMR is a public health problem, which can shake even the foundation of modern health-care.

Antibiotics are different from almost every other class of drugs in one important and dangerous aspect. The more they are used, the less effective they become. The relatively easy availability and higher consumption of medicines have led to a higher incidence of inappropriate use of antibiotics and greater levels of resistance compared to developed countries. But other factors are contributing to this crisis including the rampant use of antibiotics in livestock and poultry animals and improper disposal of residual antibiotics that eventually enter the food chain.

Research related to antimicrobial use, determinants and development of antimicrobial resistance, regional variation and interventional strategies according to the existing health care situation in each country is a big challenge.

Overview of Antibiotic Resistance and usage in India.

Studies show that resistance to antibiotics is directly linked to their usage. In 2010, India recorded a staggering 12.9 billion units of antibiotic consumption, which was the highest among all the countries. Another study conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research reveals that two out of three healthy persons in India have antibiotic-resistant organisms in their digestive tracts.

Bacteria differ in terms of the mechanisms by which they develop antibiotic resistance. Over the last couple of decades, novel mechanisms and dissemination of antibiotic resistance have been identified. Examples include the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamases in Gram-negative bacteria, AmpC (a type of beta-lactamase)-mediated drug resistance in Enterobacteriaceae, Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), and XDR Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Of late, drug-resistant mechanisms for carbapenems and colistin (which are important last-resort antibiotics) have been identified among Gram-negative organisms, and cases of colistin resistance are being reported.

Studies from India are limited, and a scaling up is essential to identify patterns of resistance as well as to quantify the nationwide mortality burden owing to AMR.

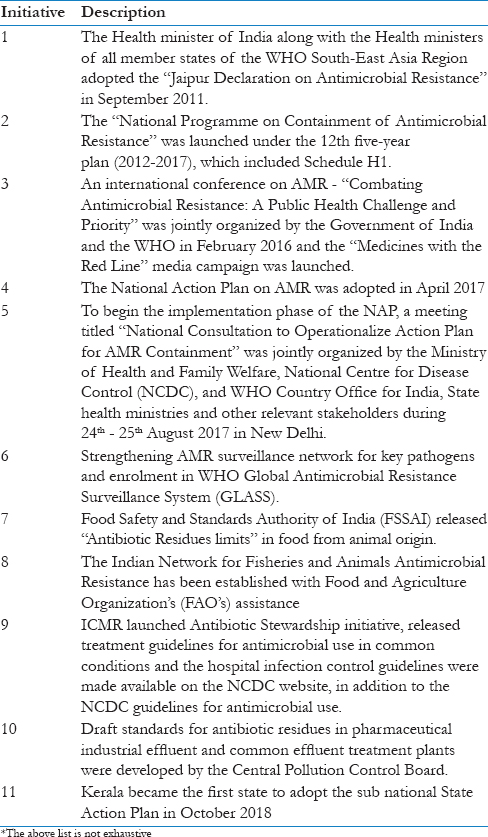

Antibiotic use is a major driver of resistance. In 2010, India was the world’s largest consumer of antibiotics for human health at 12.9 x 109 units (10.7 units per person). According to a study published in PLOS, seventy-six per cent of the overall increase in global antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2010 was attributable to BRICS countries. i.e., Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. In BRICS countries, 23% of the increase in the retail antibiotic sales volume was attributable to India, and up to 57% of the increase in the hospital sector was attributable to China.

Image 1

Image 1

Overall, ampicillin and co-trimoxazole use is declining in India, while quinolone consumption is high and increasing in India. Rates of carbapenem use per capita are low compared to other antibiotics in 2000 but had risen to over 10 million standard units by 2010.

The scale-up in antibiotic use in India has been enabled by rapid economic growth and rising incomes, which have not translated into improvements in water, sanitation, and public health, although evidence exploring this key issue is anecdotal. Antibiotics continue to be prescribed or sold for diarrheal diseases and upper respiratory infections for which they have limited value. India’s large population is often blamed for the easy spread of resistant pathogens, but population densities in India are lower than those in parts of Indonesia or China. The main problem is that India lags on basic public health measures. Immunization rates (as measured by diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis [DPT3]) coverage in India (72%) lag behind those in Brazil (95%), China (99%), and Indonesia (85%). The percentage of the population with access to improved sanitation facilities in India (36%) was far lower than the percentage in Brazil (81.3%), China (65.3%), and Indonesia (58.8%). Under the Swacch Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India Program), the government has committed to providing toilets and improving sewage systems, but these measures will take time to implement.

Challenges

Though the emergence of newer multi-drug resistant (MDR) organisms pose newer diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in India, the country is still striving to combat old enemies such as tuberculosis, malaria and cholera pathogens, which are becoming more and more drug-resistant. Factors such as poverty, illiteracy, overcrowding and malnutrition further compound the situation. Lack of awareness about infectious diseases in the general masses and inaccessibility to healthcare often preclude them from seeking medical advice. This leads to self-prescription of antimicrobial agents without any professional knowledge regarding the dose and duration of treatment. Among those who seek medical advice, many end up receiving broad-spectrum high-end antimicrobials owing to lack of proper diagnostic modalities for identifying the pathogen and its drug susceptibility. Low doctor to patient and nurse to patient ratios along with lack of infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines favour the spread of MDR organisms in the hospital settings. Easy availability of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, further contributes to AMR. The rise in the pharmaceutical sector has caused a parallel rise in the amount of waste generated by these companies. With the lack of strict supervisory and legal actions, this waste reaches the water bodies and serves as a continuous source of AMR in the environment. The paucity of data on the extent of AMR, especially in animals and environment, presents hurdles to framing and implementation of policies on the control of AMR.

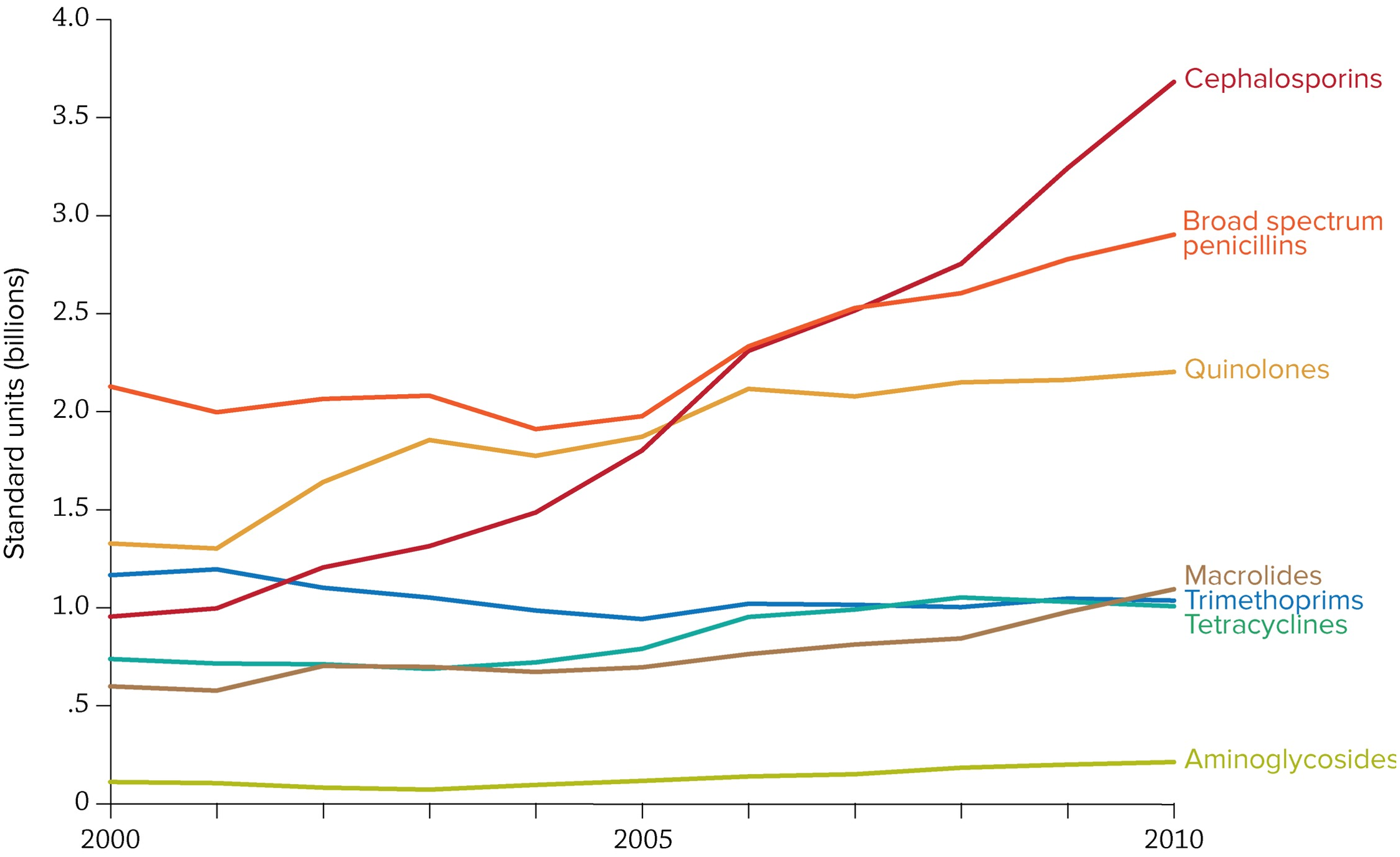

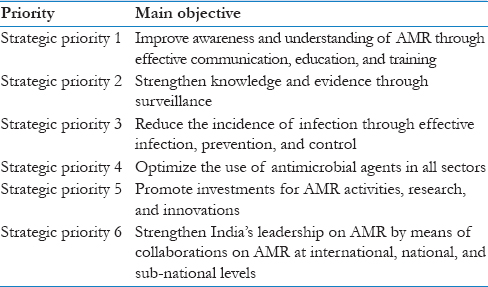

National Plan for Antimicrobial Resistance

The Indian Ministry of Health and Family Welfare published the National Action Plan for containing AMR in April 2017. It was submitted at the 70th WHA in Geneva in May 2017. This five year NAP on AMR (2017–2021) outlines the priorities and implementation strategies for curbing AMR in India. The plan proposes to target several key aspects of AMR in both human and non-human sectors (such as agriculture, fisheries, animal husbandry, and environment) incorporating the ‘one health approach’. The target periods for the components of various objectives have been listed as short-term (within 1 year), medium-term (from 1 to 3 years), and long-term (more than 3 years).

Image 2

Image 3

Though Indian NAP for AMR is a well-designed comprehensive plan that incorporates all the essential objectives of the GAP and promises to address the important policy and regulatory issues in relation to antibiotic use according to the “One health approach, implementation has been slow and a big push is needed by all stakeholders. Lack of a separate financial allocation remains the greatest challenge for the implementation of NAPs and/or State Action Plans, not only in India but also in other LMICs. Health comes under the purview of state governments. As state governments are usually burdened in managing the finances for many other schemes, the focus and fund allocation toward newer health initiatives is limited. Hence, a separate funding mechanism toward AMR with coordination between central and state governments is needed. Once the NAP is implemented, authorities should lay greater emphasis on monitoring and evaluation of all the objectives, establish appropriate governance mechanisms, and accountability to strategize how well these outcomes can be achieved in the respective settings. Hospital staff and health care professionals should enhance initiatives to promote antibiotic stewardship interventions and infection prevention and control measures as these are strategies that are completely under their control.